In Conversation: Karim Rashid

As someone who has dedicated 30+ years to making design a public subject, in combination with an astronomical number of designs in production (4000+), professional awards (300+) and exhibitions worldwide (from MoMA to Centre Pompidou), Karim Rashid needs no introduction. Numerical data and pretentious titles aside, he has always believed in the universal nature of design and that it should be accessible for everyone, regardless of the demographic. Creating better experiences for all audiences and making the products more humane and accessible has been Karim’s philosophy way before inclusivity became a trend. His designs might seem eccentric, yet they are practical, organic, and feel like a warm hug to the entire universe and humanity as a whole. Whatever Karim Rashid designs, from luxury furniture to baby bottles to sex toys, he’s repeatedly challending our physical and virtual landscape and proving that the physical world can be (and should be) emotional.

KELLY KORZUN: If anyone asked me to think about the perfect embodiment of a citizen of the world, I’d bring up your name. There’s no doubt that one of the contributing factors to your success is the fact that you’ve been exposed to a variety of cultures since the day you were born in Kyro, which ultimately forced your brain to constantly analyze the surroundings and sharpen your attention to detail. As a kid, you’ve spent a lot of time drawing together with your father and discussing design. Looking back, is there a particular conversation you had with him that you’re mentally going back to over and over again?

KARIM RASHID: My father always told me to sketch what you see, not what you think you see. Hence you look at a person, an object, or a landscape and see everything as lines, proportions, and a contrast between light and dark. Ultimately, drawing became my escape, my refuge, my meditation, and my greatest pleasure.

KK: One of the things you’ve recently discussed on your Instagram is the concept of soft/sensual minimalism. I have a theory that this need for less and appreciation for amorphous forms has to do not only with the fact that sensual design is more ergonomic, human-centric and safe, but also with the progressive development of our collective empathy and emotional intelligence. As Yoko Ono rightfully stated, although in a totally different context, Peace is Power. We don’t always have to fight in order to win. What do you think we have achieved or lost as a society during that process of fighting nature, instead of conforming to it?

KR: I believe that in order for humanity to feel some sense of immortality, it has worked perpetually against nature because it’s dystopic, random, and unpredictable. As a result, we created a Cartesian world that opposes nature’s fluidity. A cube is a perfect form, but is doing everything in its power to oppose nature. I love pure geometry, but I always realize that it doesn’t really work, and that we as humans are not meant to live in boxes and a grid-like existence. Due to the industrial revolution, everything became modular 2-D components, with the interiors and architecture being basically two-dimensional, not three-dimensional. In order to produce cheaply for mass production, many objects in our lives were based on straight lines, and now most of our built environment is 2D creating a 3D world. Today, with the help of new technologies, we are starting to be able to produce softer, more natural extensions of us and our world – we design in 3D, which inevitably creates a 4D world where time and human experience are the fourth dimension.

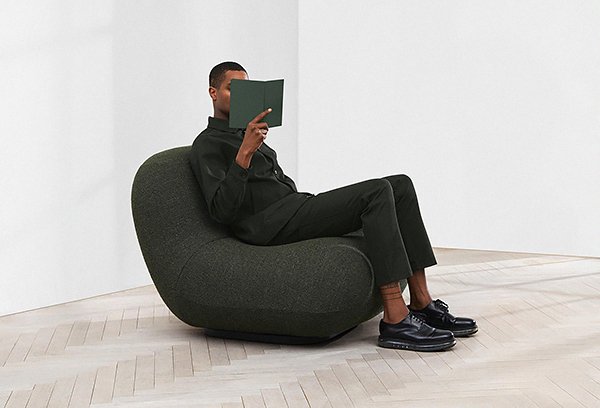

Chelsea Chair | BoConcept, Denmark (2019)

KK: Japanese designer Oki Sato who designed the Cabbage Chair for Issey Miyake back in 2007 mentioned that he likes to follow the same everyday routines because it forces you to start noticing slight differences in your environment, which can be potentially turned into idea sources. In a world where so many things have already been said and done, what do you think is the best strategy for keeping one’s work original and innovative? Is it even possible to avoid repetition?

KR: I’m the opposite. To me, routine is the demise of creativity and originality. We are born to create and are all capable of producing original work, but in order to achieve that, one must focus on the subject matter and the human experience. Today, we don’t see a lot of original work in the world because many just copy or make derivatives – few ideas, many variations. The best strategy is to not look at the same typology of your project, otherwise you will only appropriate it. Instead, look at social structures, new technologies, and human errors.

Kustom Refrigerator | Haier, China (2021)

KK: One of the most pivotal moments in your life was the day your father took you and your brother to the Expo 1967 in Montreal. Is there anything you fantasize about these days that brings similar emotions?

KR: I’ve been impressed with utopian ideas and places many times in my life. I love Esposizione Universale Roma, Brasilia, Auroville in India, and films about utopias.

KK: There are many fields that are rigid and conservative by nature, but it’s always surprised me that in medical field and healthcare money would be invested in design only when it comes to hospital equipment and the ergonomics of it, or digital products, but it would rarely be invested in interior design, although making these facilities more aesthetically welcoming would totally make sense considering that people get to spend a lot of time there while experiencing a full spectrum of emotions – from the unconditional happiness to the devastating feelings of loss, anger, or frustration. Why do you think we’re not there yet?

KR: Yes, it’s disturbing how depressing hospitals, retirement homes, and many other public spaces are so inconsiderate of good design and making life better for all of us. I think it’s starting to change since design itself has become such a public subject, but there’s always a prevailing conservativeness that I despise. The mistake is that many people see design as a superficial act, not an intellectual act. Design is a creative act, a political act, and a necessity for a better life.

Prizeotel Bonn | Prizeotel, Germany (2022)

KK: I’ve come across many young designers who aren’t familiar with the legacy of design as a discipline and the people who informed it, yourself included. They’re not asking WHY, but rather WHAT, while being solely focused on the form and eye-catching trends in design instead of the content and the narrative at its core. In order to break that Pinterest-driven mentality and highlight the importance of respecting the evolution of design, what advice would you give to young designers?

KR: Yes, I couldn't agree more. Whenever I see designs that have been done many times historically and mention blank designers or historic projects, many young creators have no idea what I am talking about. I have no idea why anyone would want to reproduce history and add nothing new to the world. My suggestion always is to learn everything you can about the history of your subject and then forget it overnight – that way you have the historic platform in your subconscious to spring forward and do something new that improves and contributes to progress and evolution, yet you are not burdened with reappearing history.

KK: Historically, many designers have been under the radar, unless there’s a crossover with popular culture resulting in mass-production, like KAWS, for example. Very few people have heard of James Rouse, the visionary developer and urban planner, but everyone has heard of Edward Norton, his grandson. Even the most influential designers and architects of all time such as Zaha Hadid, Santiago Calatrava, Albert Kahn, or Dieter Rams aren’t always familiar to the general public. What is your take on that pattern?

KR: People aren’t familiar with all these names as they’re not democratic designers, maybe except Rams. However, everyone knows Braun or Apple because the brands are being promoted, not the designers who are standing behind the brands. When it comes to the fashion industry, it’s the opposite – the designer’s name promotes the brand. I think that the general public is just starting to recognize designers, but this is a fairly new phenomenon.

Switch Restaurant Abu Dhabi | INDPT Groups, UAE (2017)

KK: Charles & Ray Eames used to operate by the conviction to never delegate understanding. As someone who’s always been inspired by technology, how would you define the healthiest relationship between technology and design?

KR: Simply put, design is inseparable from technology and innovation. If you are not innovating or using prescient technologies, you are styling, not designing.

KK: The other day my 3-year-old daughter, whose birthday is just one day behind yours (pedantic Virgo alert), was prepping for a Profession Day at daycare and asked me about what designers do, to which I replied that they make the world better because everything we use was at some point created by designers. How did you explain your job to Kiva back in the day?

KR: That is so nice. Your daughter and I were almost born on the same day! Virgos make good designers because they are perfectionists. What’s funny is that I never really explained in detail to my daughter what design is – she has just learned so much by being around me and seeing what I do. Kiva constantly comes to the studio to draw, shape beautiful things, and to think about problem-solving. She has a great talent and is extremely visual.

Nhow Hotel Berlin | NH Hotels, Spain (2010)

KK: Let’s talk about another passion of yours for a second. In 2020, Rolling Stone published the Top 10 greatest albums of all time: (1) Marvin Gaye What’s Going On, 1971 (2) The Beach Boys Pet Sounds, 1966 (3) Joni Mitchell Blue, 1971 (4) Stevie Wonder Songs in the Key of Life, 1976 (5) The Beatles Abbey Road, 1969 (6) Nirvana Nevermind, 1991 (7) Fleetwood Mac Rumours, 1977 (8) Prince and the Revolution Purple Rain, 1984 (9) Bob Dylan Blood on the Tracks, 1974 (10) Lauryn Hill The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, 1998. How far does this list deviate from what you’d put together based on your preferences?

KR: Although I love and appreciate every album listed in the list, I think that everyone at Rolling Stone is either old or stuck in a nostalgic past. There’s far better music out there, and also I don’t think it’s fair to compare different genres in a list like that. Besides, we don’t really buy albums anymore (mostly singles and best-of albums), but here is my attempt: (1) David Bowie Low, 1977 (2) Kraftwerk The Man-Machine, 1978 (3) Donna Summer Bad Girls, 1979 (4) Elvis Costello My Aim is True, 1977 (5) Giorgio Moroder From Here to Eternity, 1977 (6) Pink Floyd Wish You Were Here, 1975 (7) Poolside Pacific Standard Time, 2012 (8) Human League Dare, 1981 (9) Chromatics Kill for Love, 2012 (10) Cerrone Cerrone 3 (Supernature), 1977.

KK: You’ve visited Ukraine many times throughout your career. As a self-described nomad, designer, optimist, and someone who’s been supporting the country during these difficult times, what words of wisdom would you say to the creative community of Ukraine standing at the crossroads of essentially redesigning their entire future?

KR: Although design can be a political act, I prefer not to mix design and politics. In my opinion, we ALL collectively need to do everything in our power to avoid violence and try to make the world one with no borders or boundaries.