Talent Crush: Fabien Montique

Today is gonna be all about breaking rules, which, ironically, is a big part of Fabien’s philosophy. First off, I’m interviewing a dear friend of mine, something I’ve never done before for a number of reasons, including the risk of being biased and lacking objectivity. Second, all of my pieces start with the intro, but mentioning legendary fashion houses and iconic brands feels superfluous in this case. Lastly, I always post new content early in the week to avoid interfering with the weekend, but I knew this one had to air today, on this particular Friday, to celebrate a woman who gave Fabien the gift of life, and, in return, life gave her and the rest of the world the gift of Fabien.

KELLY KORZUN: Even before I got to know you as a person, I kept mentioning your name as one of the contemporary artists to keep an eye on: the visual language and how it’s communicated to the viewer sets your work apart from everything else I’ve seen. At one point in time, coming across a fashion magazine opened the world of editorial photography to you and transformed your life. When it comes to fashion photography, do you think that prevalence of digital editorials vs physical copies makes it less accessible to some audiences?

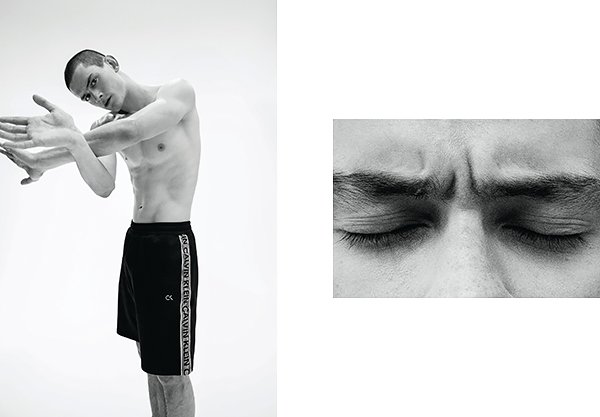

FABIEN MONTIQUE: Firstly, thank you, Kelly. As you know, I rarely do this, but I love what you are putting out into the universe, so here it goes. For as long as I can remember, I’ve always loved fashion: from stitching a Nike logo on my denim so that it matches my shirt, to seeing Calvin Klein advertisement that changed my life. Both print and digital content is a great way to show a brand’s universe and ethos, yet I prefer print. Digital has been very kind to me and holds a very special place in my heart, but turning a page engulfs me. That being said, I think it would be nice for more thought to be put into the content that end up in print. As far as accessibility goes, I’d say we have more access than ever, but consuming mostly digital information definitely takes away the feeling – we’re scanning instead of learning. As a result, you don’t get to experience the story as intended because you’re missing the full context.

© Fabien Montique x Calvin Klein

KK: During my time at Musée Magazine, I was lucky enough to work alongside Andrea Blanch, who started out her career assisting one of your heroes, Richard Avedon. What do you find especially captivating when looking at the works of Joan Didion, Jamel Shabazz and aforementioned Richard Avedon?

FM: All of them were great in different ways, but it all comes down to the human spirit and the ability to capture a moment in time when a person fully trusts the photographer to reveal their authentic self. Avedon was a true master, practically leaving no place to hide in his images: just a sitter, white background, and a rapport with the photographer is all it takes to make a great photograph. Shabazz was about capturing a culture, a cross section of people often not celebrated. I love the realism of his images, he invites you into the scene, you feel present. The images of Joan are about this ease of life, her presence without even acknowledging the camera, particularly the car series; I love vintage cars being captured.

KK: In your interview with i-D, you said that your work is an exploration of things that scare you or things you want to experience. What did you address during the past year, and what explorations are still remaining on that list?

FM: Unfortunately, I didn’t cross anything off because I worked the entire year, but I danced a lot in a studio and did a memorable trip with my brother and sister over the summer, going on vacation for the first time as adults. It started off quite rocky, but this lady at the airport saying “Hey, there is no need to fuss, you’re with your family…I wish I were with my family” put some things into perspective. Having time for personal projects is something I’m determined to change in 2023, so I’ll keep you updated.

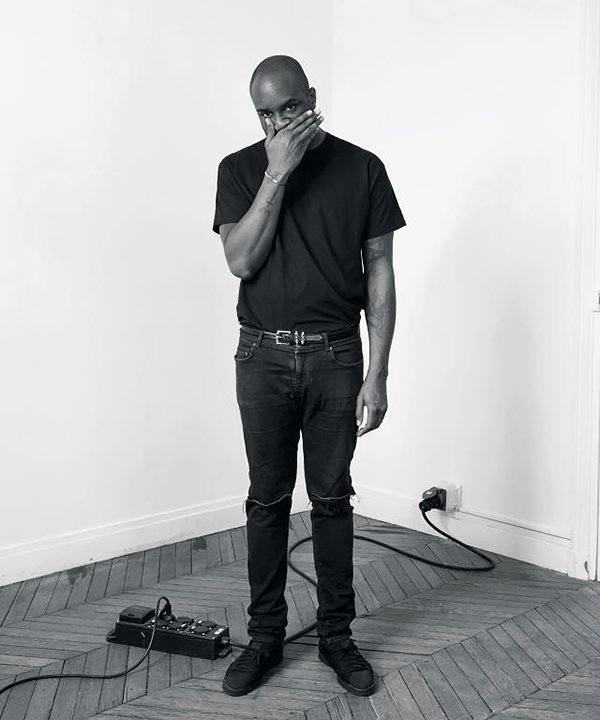

© Philip Skoczkowski

KK: How do you find the right balance between commercial and personal work, and what’s the interconnection?

FM: Growing up on an island, the struggle is to get out and stay out, so I still have that fighter mentality that everything can disappear tomorrow, and it’s not about confidence or stability, it’s just the inate and primal belief that if I am not working or contributing, I am not being correct to how I was raised. When I have time, I tend to focus on family, pets, myself and the work I want to put out into the universe, whether commercial or personal. As I shared with you earlier, I am very fortunate to see my dreams (my literal dreams) become a reality, and I am extremely grateful that I get to do things I could have never imagined. I’m constantly learning: commercial work brings resources that allow me to evolve techniques I can use in my personal work, while a better understanding of fabric, body movement, the light allows me to interject more context, representation and depth into my commercial work.

KK: Do you have any taboos when it comes to commercial work, something you’d never agree to be involved in? What’s your approach on choosing clients to engage with?

FM: Sure, there are certain filters involved such as upbringing, agency, and a gut feeling when it comes to overall energy. In photography, the only thing that makes me uncomfortable is showing violence or guns in the hands of brothers and sisters. When it comes to collaboration, my approach is to work with people who prioritize conveying the right message, showing representation, diversity, and the list goes on.

© Fabien Montique

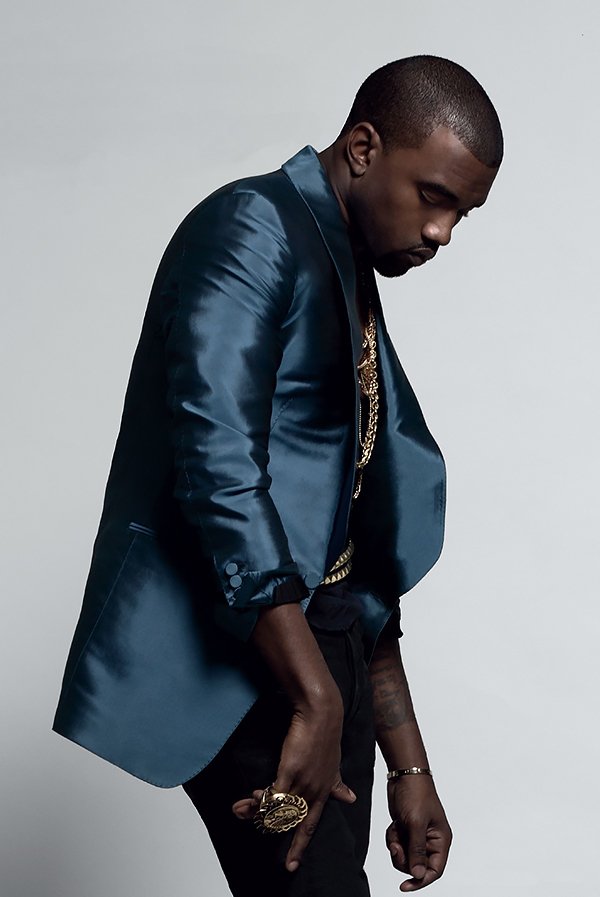

KK: Let’s talk about Figures of Speech, the first museum exhibition dedicated to Virgil’s work, brought to the audience by the MCA Chicago. After I attended the show at BkM and texted you asking how you feel about your work touring America and your name being displayed next to the works of Takashi Murakami, Arthur Jafa, and Juergen Teller, you replied: “I don't think it’s sunk in yet.” Is it because you don’t reflect on recognition that much, or because you still can’t wrap your head around the fact that Virgil is not here anymore?

FM: It’s bittersweet. He got to see it completed, which makes me happy, but on a deeper level, I always thank people and say I love you because life is not guaranteed. I always thank him, but when he passed away, I started questioning if he knew how much he meant to me. Yes, I still can’t wrap my head around the fact that he’s no longer here. I miss him so much. He was so many things to different people. Virgil put a lot a trust in me in developing visual language for Off-White, so these images carry many layers. That said, it’s an honor.

KK: I’ve spoken with a few people who knew him, from close friends to acquaintances, and it looks like he has left a positive mark on everyone he ever interacted with, which is a rare quality of one’s presence and charisma. What was the main component he brought to your work and creative process?

FM: Trust. That Kanye West era back in the day where any idea could be realized…maybe Virgil got it there too. My ride with Virgil was the closest thing to it, and it was all about trusting that you are good at your job, that you will deliver no matter what, and ultimately create something brilliant. Sometimes we would create things just to get it out there, investing in ourselves: we didn’t have money for ad placements, but we were shooting ad campaigns, making zines, etc.

© Fabien Montique x Virgil Abloh

KK: One of the things I like about free jazz is an element of the unknown that always leaves some room for your imagination. In a way, it’s like wandering the streets of the city you’ve never visited before, not knowing what’s around the corner: it could be anything, it could be everything, it could be nothing. To quote Gershwin, “life is a lot like jazz – it’s best when you improvise”, which is probably one of the reasons we both fancy Miles because he saw opportunities in situations where everyone else saw mistakes or failures. How do you want the audience to feel when looking at your photography? What kind of journey do you want to walk them through?

FM: It’s a hard one, Kelly. The reason for that is because I feel like I am still growing. I’d say hope is what I want the audience to feel and, hopefully, inspire the audience to do things they love, things that aren’t easy at first, but always bring you joy, and to do them with hard work, vision, a bit of genius, a bit of risk, and love for the work. Life should be enjoyed.

© Fabien Montique x Heroine Magazine

KK: Bill Murray’s acting coach Del Close, who was mentoring him on overcoming fear of failure on stage, said: “You’ve gotta go out there and improvise and you’ve gotta be completely unafraid to die. And you have to die lots.” What was the most challenging learning experience of your career so far?

FM: This is so true and heartfelt. You have to be willing to put yourself out there, fail or get rejected, yet be able to go back time and time again. Leaving my home at 18 to pursue this world while having no idea of what fashion meant was the beginning of this challenging and ongoing learning experience. Whenever I put an idea out into the world, whether verbally or physically, and it gets rejected for whatever reason, I try to not take it personally to a crippling stage. Sure, you always want people to resonate with the work as an artist, but the timing might be off for reasons out of your control.

KK: Today is a special day for you and your family. When you think about home in Barbados and all the memories you cherish from your childhood, what’s the food that you’re craving the most? Any special Bajan treats you ask your mom to make for you when you go back home?

FM: These early memories are mostly related to my mom, my sister, my brother, and my aunt. We are a smaller unit now, but they are always on my mind and in my heart. The food I crave the most is my mom’s macaroni pie. Whenever someone from home visits or when I am there, I ask for Bajan fruits like dungs or ackee and Bajan pepper sauce. Nothing like it. Had loads of it over the summer.